|

Understanding Extreme Geohazards: The Science of the Disaster Risk Management Cycle

European Science Foundation Conference

November 28 to December 1, 2011, Sant Feliu de Guixols, Spain

|

|

|

Bad Assumptions or Bad Luck: Why Natural Hazard Maps Fail and What To Do About It

Seth Stein

Department of Earth and Planetary Sciences, Northwestern University, Evanston IL 60208 USA, seth@earth.northwestern.edu

Robert Geller

Dept. of Earth and Planetary Science, Graduate School of Science, University of Tokyo, Tokyo 113-0033 Japan, bob@eps.s.u-tokyo.ac.jp

Mian Liu

Department of Geological Sciences, University of Missouri, Columbia, MO 65211, USA, lium@missouri.edu

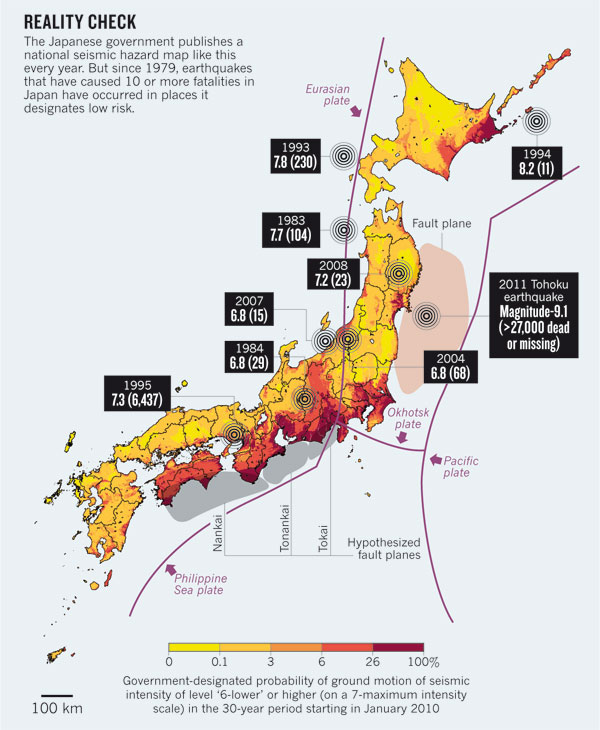

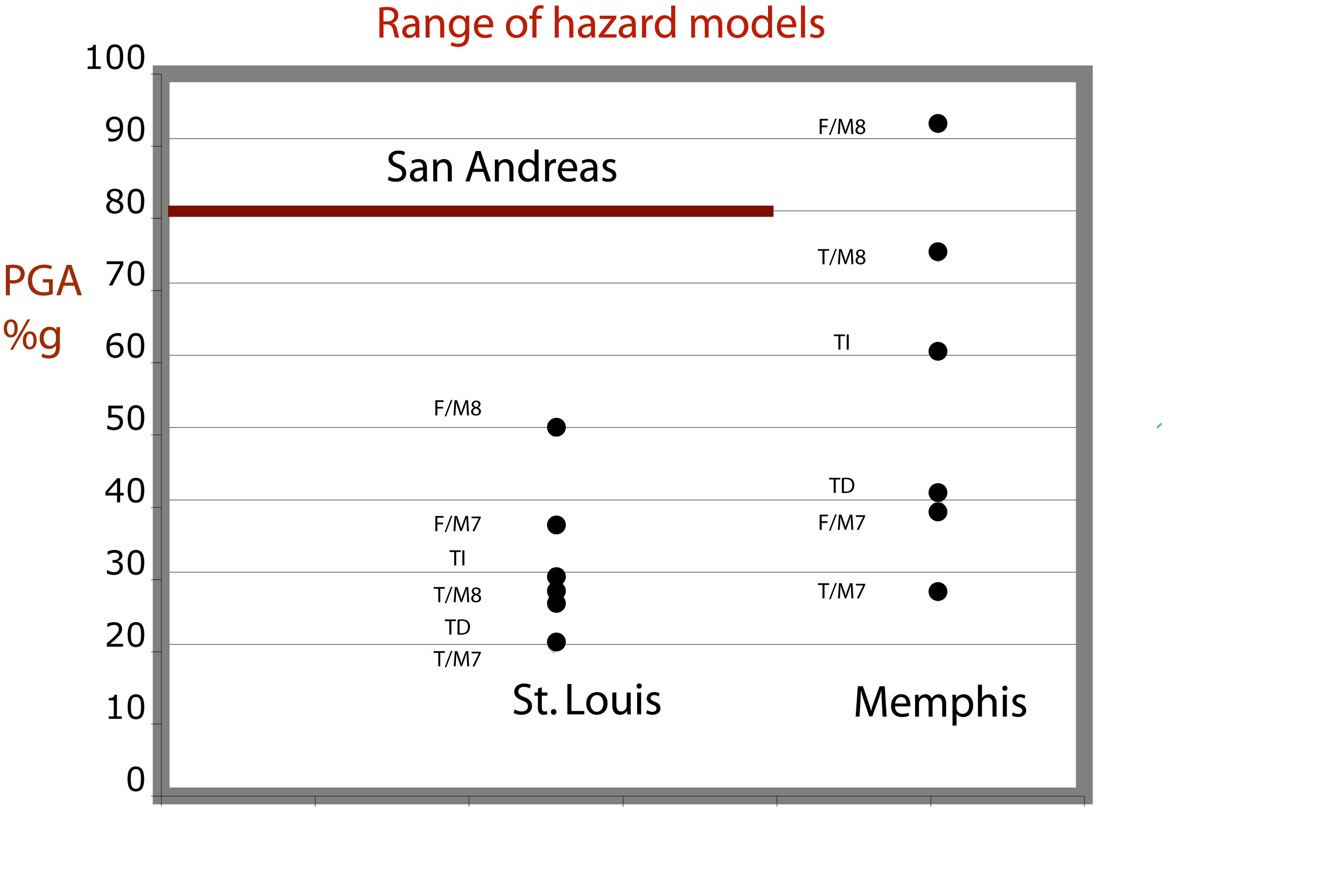

Important tools in preparing for natural disasters include long term forecasts, short term predictions, and real time warnings. How well these can be done for different disasters - earthquakes, tsunamis, volcanoes, storms, and floods - differ dramatically, calling for careful analysis. The challenge is illustrated by the 2011 Tohoku earthquake. This was another striking example - after the 2008 Wenchuan and 2010 Haiti earthquakes - of highly destructive earthquakes that occurred in areas predicted by earthquake hazard maps to have significantly lower hazard than nearby supposedly high-risk areas which have been essentially quiescent. Given the limited seismic record available and limited understanding of earthquake mechanics, hazard maps often have to depend heavily on poorly constrained parameters and the mapmakers' preconceptions. When these prove incorrect, maps do poorly. The Tohoku earthquake and its tsunami were much larger than expected by the mappers because of the presumed absence of such large earthquakes in the seismological record. This assumption seemed consistent with a model based on the convergence rate and age of the subducting lithosphere, which predicted at most a low M 8 earthquake. Although this model was invalidated by the 2004 Sumatra earthquake, and paleotsunami deposits showed evidence of three large past earthquakes in the Tohoku region in the past 3000 years, these facts were not incorporated in the hazard mapping. The failure to anticipate the Tohoku and other recent large earthquakes suggests two changes to current hazard mapping practices. First, the uncertainties in hazard map predictions should be assessed and communicated clearly to potential users. Communication of uncertainties would make the maps more useful by letting users decide how much credence to place in the maps. Second, hazard maps should undergo objective testing to compare their predictions to those of null hypotheses based on random regional seismicity. Such testing, which is common and useful in other fields, will hopefully produce measurable improvements. There are likely, however, to be limits on how well hazard maps can ever be made due to the intrinsic variability of earthquake processes.

|